Prac Crit

The Ballad of R. D. Laing

by Conor Carville

Interview

by Matthew Sperling

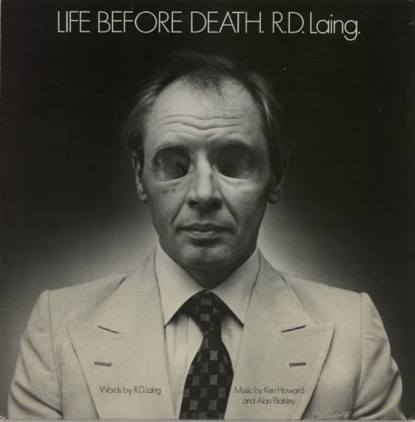

‘The Ballad of R. D. Laing’ by Conor Carville, which is published for the first time in Prac Crit, takes a specific image as its point of departure. The poem’s speaker, browsing in a charity shop, makes the chance find of a copy of Life Before Death, the 1978 LP issued by Charisma Records, which features poems by the Scottish psychiatrist R. D. Laing set to music by composers Ken Howard and Alan Blaikley (the album can be heard in full online). He looks at the rather terrifying image on the sleeve of the record, created by photographer and ‘combination printer’ Hag.

Starting from this image, located in a specific cultural moment when ‘poetry and psychiatry / shacked up for a time’, the poem follows a madcap route through ten stanzas, drawing in a wild array of historical remnants from anthropology, psychiatry, electronic music, SF and private memory.

Conor Carville’s first book of poems, Harm’s Way, was published by Dedalus Press in Dublin in 2013. In the online magazine Partisan, I wrote that Harm’s Way

is a first book of inspiring range and confidence, traversing cultural history and global modernity to find figures for harm and love, and shaping them in a language of weird substance and full song. It introduces a poet who can out-Muldoon Muldoon across a run of rhymes (‘unveil’ / ‘musique concrète’ / ‘gazelle’ / ‘Serengeti’); can whip up a jovial hullaballoo about a wheelie-bin (‘Flibbertigibbet. Comes back / empty but for the filth / that furs its gullet, the tilth / of swarf and milt impacted…’); can turn Walter Benjamin into Columbo, ‘grizzled possessor / of the shonkiest raincoat in Los Angeles,’ then send him on a journey through ‘the twentieth century’s / demented spaghetti junction’; and can close his book in graceful encounter with Minerva, goddess of wisdom, art, trade, and strategy: ‘the man lying low / in cahoots with the owl // who is wearing his head / the other way round.’

‘The Ballad of R. D. Laing’ carries forward many of these qualities: the eclectic learning, the inventive rhyming, and the phrase-making that ‘come right with a click’, to quote a phrase from the poem (channelling W. B. Yeats’s idea, expressed in a letter to Dorothy Wellesley, that ‘a poem comes right with a click like a closing box’). And it gives freer rein to what Conor calls the ‘headlong, propulsive quality’ of his writing, working on a larger scale than the poems in his first book.

Conor is also the author of a scholarly book, The Ends of Ireland: Criticism, History, Subjectivity, published by Manchester University Press in 2011, and teaches English and Creative Writing at the University of Reading, where we were colleagues from 2012 to 2015. This interview was conducted by email in June 2016, while I was in Berlin and he was in London.

| MS | Could you tell me something about the attraction of R. D. Laing as a figure? It seems to me there’s been renewed interest in Laing and ‘anti-psychiatry’ in recent years. |

| CC | Well he’s someone I’ve been aware of for a long time. I read at least some of The Divided Self in Dublin when I was in my early twenties, and later I read the biography. Then in the early Nineties, when I moved to London, I noticed that whenever I went into a charity shop – and I did that a lot – there would always be at least one copy of Laing’s poetry book, Knots. Always. I don’t know why that was, perhaps it’s just that it was so bad that everybody who bought it off-loaded it. But why did so many people have it in the first place? Anyway, that intrigued me. It was like this constant, dog-eared, damp-stained remnant of something that had happened before my time. So there was something weirdly potent about the book, not due to what it said, but as an artefact. It was somehow charged and talismanic, like a Heaney object, except not a farming implement. A trace in the collective memory. I agree that there is a lot of interest in Laing now, just as there is in people like Ballard, or Anna Kavan or Ed Dorn. It’s part of a dawning realisation that the moment in which those people emerged was the tail-end of a distinct historical period that is now definitively over. There’s a lot of conscious, curatorial retrieval of the 70s as a result. The exhibition about the Themersons at Camden Arts Centre at the moment, for example. Or Luke Fowler’s films about Laing and Cornelius Cardew. But I guess I’m more interested in unconscious retrieval. |

| MS | You mention Heaney – a Northern Irish poet can hardly begin a poem with the word ‘Between’ without recalling ‘Digging’, and the now-commonplace idea of Heaney as ‘a poet of the in-between’. But whereas Heaney’s talismanic objects give access to personal meanings that seem authentic and rooted, and to provide origin-myths for his own consciousness, your poem is more interested in accessing memories that are cultural and mediated by specific technologies, and they lead to an encounter with a mysterious other: ‘eyes that are not mine’. Were you writing against that idea of the Heaneyesque encounter with an object whose significance is personal? |

| CC | It is hard to overstate the significance of Heaney for me. Growing up where I did, he was a kind of fixture, and everyone, absolutely everyone, knew who he was. It seems strange now that the most immediately visible writer or artist in the public sphere should be a poet, but that was the case, and his presence also meant that writing poems seemed an eminently sensible thing for someone like me to do, which is, needless to say, also very strange. Heaney was of the exact same generation and background as my parents, and so I also recognised a lot in the content of the work. And yet my own experience was very different. For example, I very vividly remember as a child spending Saturday afternoons going to visit my great-uncles, my grandmother’s two brothers, who lived on a small farm a couple of miles outside the town where I was brought up. Neither of them had married, and they lived in a long low whitewashed cottage, with a clay floor, no electricity, a pump in the yard and so on. The kind of existence that had not really changed for centuries. Heaney territory. We’d stay a few hours then drive back home, and on the way there would inevitably be an army checkpoint, paratroopers in camouflage facepaint with carbines and walki-talkies. After that we’d rush on so as to get back in time to see Dr Who, and my brothers and I would spend the next half an hour happily watching Tom Baker stagger around a space station with his face covered in slime. That journey took about 10 minutes, from Irish peasant life, through an encounter with state of the art military power to the strange pulp modernism that the BBC was producing in the 70s. And I have no doubt that it was the latter that had the most profound effects, so that everything else was filtered through a sensibility engorged and warped by popular culture. And it was of course British popular culture. So yes that mediation is something I am interested in. But I’m not consciously writing against Heaney. Indeed Heaney’s poetry acknowledges mediation too. In the bog poems he is looking at photographs after all. And in fact, though I can’t prove this, I remember shocking mass-produced posters that were put up after one particularly horrific fire bombing, posters that featured the twisted, burned bodies of the victims that might have triggered the associations Heaney sees in the Danish images. But you’re right of course, there is a strong chthonic strain in his poetry, and also an absolute commitment to memory as a kind of redemption: ‘My last things will be first things slipping from me’ as he says in ‘Mint’. Those memories always seen to be delicate and beautiful for Heaney, whereas I worry that the last thing I’ll think of will be the winning song of the 1978 Eurovision. |

| MS | Yes, I like how jumbled the cultural artefacts that make their way into the poem are. Sometimes they seem linked by unconscious associations – in the first stanza alone, alongside Laing’s album-cover, we get allusions to Martin McDonagh’s A Skull in Connemara, T. S. Eliot’s line on John Webster as a playwright who ‘saw the skull beneath the skin’, Magic Eye images, the duck-rabbit made famous in Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations… It’s like the logic of the charity shop combined with the randomness of memory. But the poem also seems drawn to different, older systems by which artefacts have been ordered: the columbarium in stanza one, with its neat pigeonholes for the remains of the dead; the library in stanza six; the Museum of Mankind, i.e. the old ethnographic department of the British Museum, in stanza 10. It seems, ironically, like a very internet-age concern with how cultural memory is stored and retrieved. |

| CC | I’d forgotten about the McDonagh play – I actually took that phrase, as he did I suppose, from Lucky’s epic rant in Waiting for Godot. Lucky is a kind of slave, a subaltern figure, and his speech is in response to his master Pozzo, who commands him to ‘Think, Pig!’. So there’s a parody of rational thought, and of rational ordering of thought, in the speech. But then these other, weird elemental images start to break through at the end, including the skull in Commemara, an ‘abode of stomes’ and, strangely but wonderfully, tennis. When its performed well it’s astonishing, but what I love is the headlong, propulsive quality that builds up, the way Beckett uses repetition to really get up a head of steam, so that the language seems to gradually colonise Lucky, take him over. He becomes a kind of prothesis being used by this abstract, onrushing discourse that has lost its moorings in reason and is functioning purely mechanically. I suppose I wanted some of that quality in the poem – when I read it I tend to speed up as I go along, and hopefully the repetitions and the rhymes give it a sense of rapid permutation and automatism. But on the other hand the form of the poem, the ballad form, is itself a kind of ordering, with its own authority and its roots in song and orality and the commons, and I definitely wanted to tap into that. Now I think of it, the title came to me first, and I liked the idea of bringing together a folk form with a resolutely modern figure. I guess the title of John Lennon’s The Ballad of John and Yoko was somewhere in the back of my mind. Now I’m toying with the idea of a The Ballad of J.G. Ballard, which will be mostly about traffic bollards. What you say about the internet is intriguing, because again you put your finger on something that does inform the poem at some level. One of the things that attracts me to the album cover for Laing’s Life before Death is how crap it is as an image. It’s really crude and badly made by today’s standards of digital manipulation, where it would be absolutely seamless. Its what the artist Hito Steyerl calls a poor image, one at odds with the slickness of the digital. We’re now in the era of the fold and the warp rather than the cut and the collage, and as a consequence online space seems to me to be much more of a continuum rather than the antagonistic space of the junk shop or the disused shed. It’s true that both are spaces where a thought might grow, but the formal distinction between the internet and the charity shop, conjunction and disjunction, will affect the nature of that thought. I’m very interested in having those two strategies of relation in a poem, where objects, images and ideas are juxtaposed but also suspended in a kind of solution that connects them. Ashbery is brilliant at it. |

| MS | Beckett, of course! That one passed me by because the McDonagh play has thoroughly buried Waiting for Godot on the first page of the Google search results for ‘skull in connemara’. So much for the internet… I’m interested that you mention the ‘authority’ of ballad form. It reminds me of how Derek Mahon worries in his Paris Review interview that talking about form and authority leads one towards ‘dangerous waters’. Rhyme, and a certain relation to traditional forms, are obviously very important in this poem and many of the poems in your first book – what are your thoughts on rhyming in the twenty-first century? |

| CC | I imagine Mahon is thinking about Yeats and the way he associated certain forms, like Spenserian stanzas or ottava rima (‘stadium stanzas’ as Paul Muldoon calls them), with power and purity, an antidote to what Yeats himself called the heterogeneity of the twentieth century. Yeats thinks forms like those can give a traction on modernity, so that the poet can stand outside it. This, paradoxically enough, is what makes him a modernist – the idea that, through the manipulation of form, art can tear through the veils and return us to a more authentic notion of the real. It’s impossible of course, there’s no outside, and the kind of passion for the real you find in Yeats and Pound and Wyndham Lewis certainly did lead to some politically dodgy territory. That’s all over, or should be, although there are still those who base their aesthetic around varieties of it, of that idea of a complete break, whether by returning to some illusory past, or some authentic experiential present, or some revolutionary beyond. So I have no illusions about this form or that form being innately authoritative or meaningful in that kind of a way. But I do think that the popular forms that emerge from below, so to speak, whether it be the ballad in the past, or the music you might hear on pirate radio or on somebody’s mobile on the bus have, as I said earlier, their own kind of authority, stemming on the one hand from being collective and often anonymous, and on the other from being constitutively impure and totally omnivorous. I guess by authority I mean they contest or negotiate more mainstream ideas, while always being deeply entwined and beholden to them at the same time. Something like the popular, vernacular ballad, as it develops, is always completely shot through with elements of the social and cultural formations it seems to be opposing. This is especially obvious in colonial situations, but it happens everywhere. So while there is no pure outside to the contemporary into which one can just leap, what can happen is a kind of miming and staging of the fractures and fault-lines that ramify through every social situation. Popular forms do that I think, they have a kind of agon running through them that mirrors the antagonism of the world, and I’m very interested in those kinds of possibilities. And, to finally answer your question, rhyme is a part of that miming. One often hears the cliche that rhyme is everywhere, and that that indicates the health of poetry. But it is less often acknowledged that the forms in which rhyme appears are kind of degraded, they are popular, subcultural, kitsch – rap and grime, graffiti, football chants, home-made banners, jokes, birthday cards, nursery rhymes. But then given what I said earlier this makes total sense, because if you are looking for a formal model of repetition with a difference, a formal demonstration of the subcultural or popular process of taking a standard or norm and progressively changing and twisting it and making it your own, then rhyme is perfect. That’s what rhyme does: it’s performative, iterative, it sets up a pattern and then rings the changes, as they say. Or certainly that’s true of the kind of rhyme that I am interested in – half-rhyme, slant-rhyme, eye-rhyme, internal rhyme – subtle variations on a single rhyme across extended stanzas, or even across a whole poem, which I also enjoy doing. |

The Ballad of R. D. Laing

by Conor Carville

Between the skull in Connemara

and the one beneath the skin,

lies the album sleeve aglimmer

in the bargain-columbarium

of a charity shop in Banglatown,

Banglatown or Stepney,

the skull that glows, all unbeknown

where poetry and psychiatry

shacked up for a time, their Magic-Eye

polarities in strobing flux:

as duck scuppers bunny,

so bunny morphs to duck.

I tug it from its berth in the depths,

twig as the legend appears

above the image: Life before Death,

in a 70s font, some weird

Bodoni or Didi, underneath it your

protophotoshopped

head, a double exposure of spirit

and bone, empty sockets

craftily superimposed

on greyscale skin

like two osculated snow-globes

pimped to a cultic bonce.

Slanting the cover I peer again

at the funny head, following

each orbit’s rim to the deskilled join

where sinkhole

eyes are counter-sunk to throw

ripples of flesh through

a mandarin’s forehead. Below

are swags of adipose

that fall away into the shadows

massing inside the coombe

of your scooped-out brain-bowl:

bereft of lobe; gunk-lubed.

The innermost sleeve slides out

okay but the disc is unfeasibly

scundered, a crockery of claw-

marks and keratotic lesions

with maximum haggle points; also

there’s the clammy

tang of some kind of decomposing

linctus released,

infusing swaying nostril groves

with memories of my Father’s

clothes at breakfast, home

unspeaking from Special Care.

I see cut-ups and duct-tape, Krapp

at his tape-deck

manipulation. Delia spooling a loop

while Burroughs prospects

along the bloody seam that opens

on his desk between

two columns, the self-same

broken line that steals

along the hominoid cranium’s

basal ridge, where

the reptile brain teeters upon

the haunch of my shoulder.

I think of the golden portal-plates

of Tutankhamun’s death-mask,

the infinite reticence of its face

weighty as a star impressed

on the laminated library book I scored

in a memorable foray

deep into the Paranormal

aisle while Granny was away

hoking and execrating in Needle-

Craft. Also in that haul

the spin-off paperback from Arthur C. Clarke’s

Mysterious Worlds.

Its cover’s crystal Aztec skull

ascends now like a new-born

planet above the white

horizon of my brain

as I assume the position and someone

removes my head, setting

it down upon the floor, its little gown

of bloodied polyps notwithstanding,

from where it can watch and laugh

and sing this air

as the skull of R. D. Laing

bestirs itself and is prepared.

The album-cover skull extrudes. By degrees

it eases up with

mycological growth, it creaks

against the flattened image of itself,

becoming first a bas-relief and then

a peaky death-mask

that is prized from its station

to stand in the round, fully plastic

at last and held solemnly

above the stiff upstanding

void of my neck, onto which it is carefully

threaded: turning, turning.

Turned and turned like the tricky

anti-tamper cap on

a bottle of tricyclics:

Clozapine, Aripiprizole (contra-

indications might comprise

sexual panic, Neanderthal

phonics) screwed down until

it comes right with a click,

and the eyes that are not mine

light up to look around

and catch my own bright eyes.

That hesitate. That cast themselves down.

The eye cast down, the cast in the eye

of a shrunken head

in The Museum of Mankind.

The bright bone shelled

from such a skin, clean as a conker,

seat of the soul. The whole

kit and caboodle reduced

to a sponge on the spear

of the spine: a totemkopf, hopped up

on dopamine; the sallow rebel,

spiked on a pole above the portcullis,

halfway to becoming a skull.

First Published by Prac Crit.