Prac Crit

from ‘The Rat-poison Man’s Lunch Hour’

by Arun Kolatkar

Wayside Inn

by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra

Giving the new feature its name, this essay is the first in our ‘Wayside Inn’ series, where writers read a poem from the past…

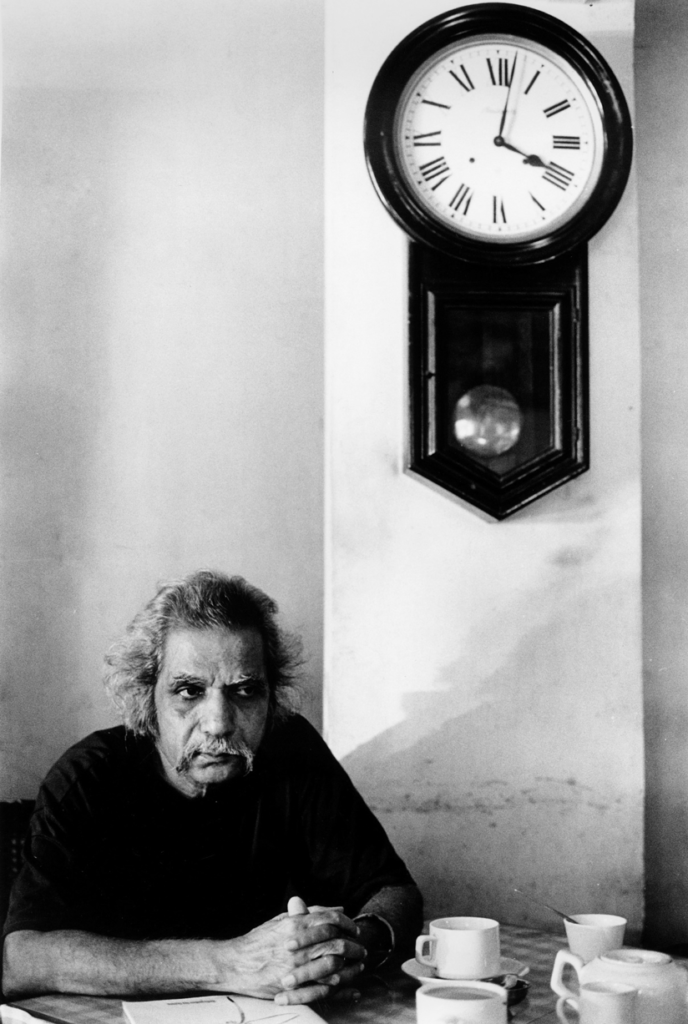

On the cover of Arun Kolatkar’s Collected Poems in English (Bloodaxe, 2010) is a photograph by Madhu Kapparath, one of several he took of Indian poets at work and at play in the 1990s. In it, we see Kolatkar seated at his favourite table in Wayside Inn, Rampart Row, Bombay, the restaurant where he was something of a fixture for close to four decades. Before him, on the gingham tablecloth, is a white ceramic tea set: two tea cups with saucers, a tea pot, a sugar bowl, a milk jug. If Kolatkar had been looking at his clasped hands rather than to one side, and if, in his hands, he had held playing cards, he could be a study for Cezanne’s The Card Players. But Kolatkar seems to be looking towards the window. His expression is of someone who is both there and not there, both inside the restaurant and outside it, where he is observing the life of Kala Ghoda, its crows and its dogs, and its men, women, and children. On the peeling wall behind him is a grandfather clock. The time is two minutes past four; tea time.

Though in the Kapparath photograph he is sitting alone, Kolatkar appears to be listening to someone. He is listening to the walls of Wayside Inn. The stories they tell have to do with the history of the place, now somewhat in decline, though no decline was visible on the faces of its ageing waiters when they took your order. Wayside Inn, the walls tell us, was once a hat shop:

The wall can talk about an old hat shop

that doesn’t even exist any more.It can talk about cheerful red-checked tablecloths,

blue Delftware and rose windows,cut-glass vinegar bottles with round stoppers

and antique silver-plated cruet stands.

Next to it is Rhythm House, whose music the restaurant wall ‘remembers . . . from the thirties onwards / – from Saigal and Bessie Smith to Guns and Roses.’ More and more, the wall begins to look like a chatty customer. Kolatkar, it seems, is having tea not in but with Wayside Inn. The songs coming from Rhythm House create, in the wall, ‘new neural pathways.’ Instead of ageing, the wall’s brain cells regenerate, hence the new pathways.

It remembers Babasaheb sitting all by himself

with a pot of tea and scribbling notes,dreaming with an audacious pencil

of a society undivided by caste and creed.It remembers an obscure poet munching on Welsh rabbit,

and thinking of rats dying in a wet barrel.

In these stories that the restaurant wall tells are to be seen, as perhaps had not been seen before, three distinct yet intertwined modernities: the modernity of the Westernized Indian city whose restaurants have blue Delftware and silver cruet stands; political modernity, with the reference to Babasaheb Ambedkar and his audacious dream of a new society ‘undivided by caste and creed’; and literary modernity, with the reference to ‘an obscure poet’, BS Mardhekar, who dreamt of a new kind of Marathi poem in ‘Pipat mele olya undir’, where the dominant image is of rats dying in a wet barrel: ‘Like rats, they died in a wet barrel. / Their heads rolled, though no one had wrung their necks’ (translated by Vinay Dharwadker).

The Kolatkar quotations above are from the fourth section of ‘The Rat-poison Man’s Lunch Hour’ in Kala Ghoda Poems. The poem’s opening lines, and indeed most of the poem, are not about the restaurant’s past and its distinguished clientele but about what is going on outside, in the present. Now we see why Kolatkar, in the photograph, appears both seated at his favourite table and not there at all. To the three modernities mentioned above, he adds a fourth, that of the Indian street, which is little noticed by most people because everything in it is so overwhelmingly noticeable:

The rat-poison man has left

his one-legged poster leaningagainst the wall of Wayside Inn

and settled down for lunch on the pavement . . .

Kolatkar had a rippled imagination. He cast a pebble into the lake of poetry, then sat in a restaurant with a cup of tea and watched the ripples expand. In this case, they expand to encompass what was once a new nation. What has become of it is another story, and Wayside Inn is no longer there to tell it.

from ‘The Rat-poison Man’s Lunch Hour’

by Arun Kolatkar

1

The rat-poison man has left

his one-legged poster leaning

against the wall of Wayside Inn

and settled down for lunch on the pavement,

with his back to the poster,

in the polyphonic shade of the banyan.

The dejected poster stands

facing the wall as if it has been punished,

hiding its real thoughts

and showing its blank,

unsized and uncommunicative side

to passers-by.

An expressionless oblong of white canvas

stretched on a wooden frame,

with a wooden bar that divides it

vertically in two equal halves

and continues past the base

to form a short stumpy leg

with a chunky three-inch wheel

grafted onto its club-foot,

the whole construct designed

never to challenge

the average Indian male

vertically.

2

The poster shows a dozen rats

emblazoned on an azure field.

Some dead, some dying,

in various stages of agony.

Black, brown and grey rats.

One a rare blue at dexter base.

Some have tails like corkscrews,

some like unrepentant awls.

At peace at last

with their incisors

(or do they keep growing

even after death?),

their whiskers are sharp

like poison-tipped needles,

and they all seem to glow

with an electric blue aura,

a kind of

radioactive nirvana.

3

Foreheads touching,

they exchange paranoias,

share anxieties, confidences, histories, hopes

– with a total lack of comprehension.

With its peeling paint and plaster,

the wall offers what consolation it can,

but it fails to understand

the hate-filled world of the rat-poison poster,

its obsession with death

– the only truth it seems to know –

its vision

of the final battle between good and evil,

fought bitterly in two dimensions,

with cheap enamel paint and biological weapons,

with a clearly defined enemy

and a clear plan of action.

4

The wall can talk about an old hat shop

that doesn’t even exist any more.

It can talk about cheerful red-checked tablecloths,

blue Delftware and rose windows,

cut-glass vinegar bottles with round stoppers

and antique silver-plated cruet stands.

Boy meets Girl at the Corner Table

is a story it never tires of telling,

and remembers all the old songs from the thirties onwards

– from Saigal and Bessie Smith to Guns and Roses –

as new ones keep percolating from the music shop next door

and creating new neural pathways in its cement.

It remembers Babasaheb sitting all by himself

with a pot of tea and scribbling notes,

dreaming with an audacious pencil

of a society undivided by caste and creed.

It remembers an obscure poet munching on Welsh rabbit,

and thinking of rats dying in a wet barrel.

That’s the only bit the poster understands,

dismissing everything else

as so much bullshit mousse and sentimental custard.

It even suspects that the wall,

spongy with nostalgia,

may actually have a soft corner for rats.

5

A lawyer walks into Wayside Inn

softly humming ‘Aasamaa pe hai khuda’,

is glad to see that his favourite table

is empty, orders a beer, takes a sip

and, licking the foam off his upper lip

contentedly, leans back in his chair,

which brings the bald patch on his occiput

in direct contact with the exact spot

on the inner side of the wall

that’s in touch with the rat-poison poster.

The wall’s good enough to provide him with

the words to the second line of the song

that he has been trying to remember all day;

and the poison poster’s only too happy

to secretly plant the seed of a deathwish

in the lawyer’s head without his knowledge

– a seed that will take its own good time

to germinate, but germinate it will.

6

A dismissive flick of his little finger

slices the top off a hill of rice.

A few quick jabs of fingertips,

and a crater opens before him.

The woman in a plain red nylon sari,

choli to match and hibiscus in hair,

dips a ladle in an aluminium vessel

that sits with a sooty bottom on a Primus stove,

and tips it over the steaming crater.

The hill collapses on itself,

volcanic sambar starts oozing out

of fissures that open in its south face.

*

Whoever he is – her husband, pimp, cousin –

the woman has a lot to say to him,

for she has been doing all the talking,

as the two of them sit under the banyan

on the opposite sides of the same thali,

and he has been nodding from time to time,

mechanically, as he sends volley

after volley of fire-and-forget riceballs

in the general direction of his face,

without cease or let.

*

A riceball leaves, or rather, slips out of his hand,

as soon as his fingers have formed it;

it gathers speed as it rises,

gets past the defences of his beard,

blasts a gaping hole in his face

– even before it can be hit –

to burst in his mouth

and to zap him on his palate.

*

As more and more rice

is transferred to his belly,

the thali, too, begins

to nod along with him;

imperceptibly at first,

and then quite vigorously

– in unconscious imitation of the man,

perhaps, or may be because, by now,

the thali, too, has really got involved

in what the woman has to say,

or may be because the steadying influence

of the rice is fast disappearing

until, towards the end of the meal,

it rocks so violently

that the man has to hold it down,

physically, with one hand,

so that he can make

a clean sweep of it with the other.

*

The woman pours some water from a mug

for the man to wash his hands in the thali,

which produces a passable drum solo,

to act as a coda to one man’s lunch.

They both get up; he says something to her,

pats her affectionately on the bottom

as she bends to pick up the sloppy thali

and he turns away to reclaim his poster;

and holding it before him like a shield,

is ready, once again, to face the world,

happy, once again, as who wouldn’t be,

with a singular truth to hide behind.

from Arun Kolatkar: Collected Poems in English, ed. A.K. Mehrotra (Bloodaxe, 2010); reproduced with the permission of Bloodaxe Books.