Prac Crit

Hummingbird

by Sylvia Legris

Essay

by Rachael Allen

Here are some facts I learned about hummingbirds while reading Sylvia Legris’s ‘Hummingbird’ triptych. I learned that hummingbirds’ hearts are in relative terms the largest hearts of any animal (making up 2.5% of its weight), that this same heart beats 250 times a minute, that their reproductive organs shrink to a small fraction of their usual size when not in use, that they’re attracted to the colour red, that they have eyelashes and massive pectoral muscles but poorly developed feet. Strange and monstrous differences to us, things that all sound to me like typical poem fodder, perhaps. The alien notion of a bold non-human animal suffering through life with these inhospitable differences (mad heart palpitations, difficulty strolling to choice nectar, etc), while hosting certain irresistible similarities to us, is bound to tempt us to anthropomorphise, as we shoehorn the cute aspects of the hummingbird (big heart, eyelashes) into a poem of broad realisations about our human selves.

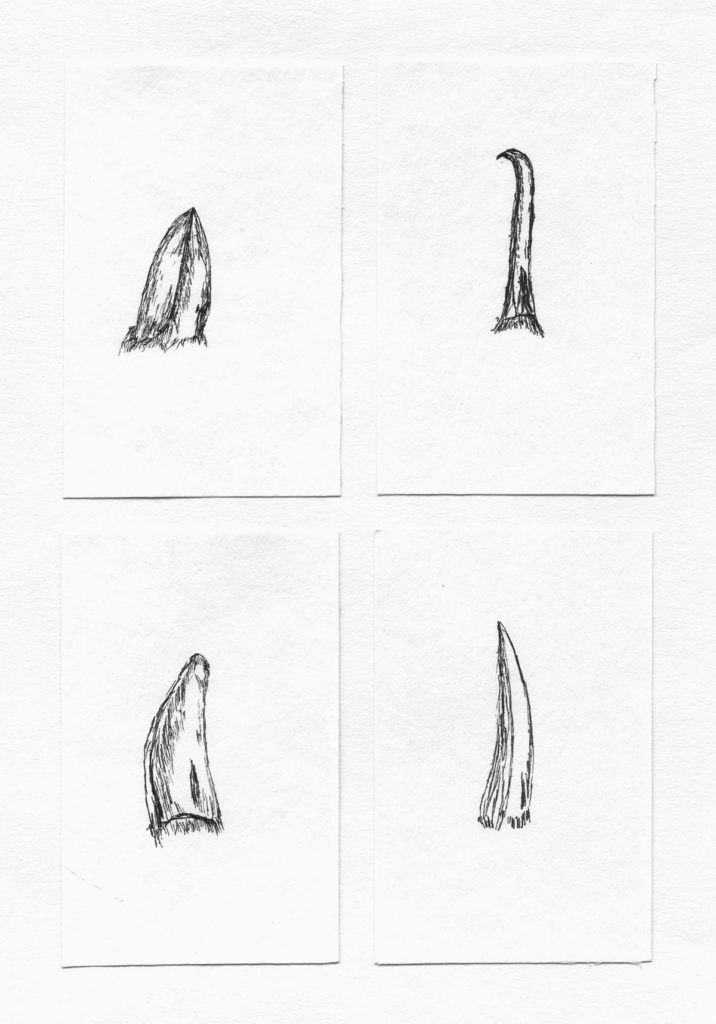

Image by Sylvia Legris. First published in Pneumatic Antiphonal (New Directions, 2013)

How do we write poetry about animals? We have been doing it for a very long time, and for a very long time, on the whole, this poetry has had far more to say about us – foregrounding our peculiarities and our concerns – than the animal. To be sure, such self-involvement is hard to avoid. Poetry often acts as a mirror to the strange hypocrisies and disregard we practice with the animals in our homes (dead cow in the fridge, loved cat on our laps, feared lion on the telly). We use their bodies for meaning, their history for emphasis, their flight patterns and trails to articulate our aesthetic concerns. And it is birds that seem to get the most attention and, simultaneously, the roughest deal. They basically exist as symbol and metaphor. In the more careless poems, the bird’s song or just plain existence works as function, robbed of its actuality. The lineage of poets using bird song is long and canonised; so many have either wistfully clutched at the slippery noise of birds singing, or attempted to interpret poetically the feeling of just being in their midst. They’ve tried to catch the indefinable, or acknowledge the indefinable through attempts to define it, some with more care than others.

*

When you listen to a hummingbird sing and fly, it sounds like something between a bee malfunctioning and a computer with a broken fan. It’s not so ‘beautiful’ a noise as, say, a nightingale singing in Berkeley Square. Legris’s three ‘Hummingbird’ poems take their place in a longer sequence that makes up her pamphlet Pneumatic Antiphonal, 45 pages of analytical, comprehensive and exhaustive description of birds’ song. This is decidedly not ‘music’ to take pretty delight in, and Legris reproduces it as such. It’s examined and methodically re-written by a human as though for a museum catalogue: non-human animal music wrought technically, linguistically. An interpretation or translation of sorts, it is a patient attempt to show birds’ song sounds as birds’ song, in words. She fails, in as much as all poets fail when attempting to show something as it really is, yet her failure seems intentional, designed to illuminate the spectacular, endless potentials of turning sound into a description of what a sound sounds like. In the space of this failure something brand new emerges, the described sound becoming completely alien and unlike the actual thing. The pamphlet is one long experiment in the game where you have to try to describe how a song sounds to somebody who hasn’t heard it – utterly impossible, yet in that impossible void a brand new song is made, the one you want to exist, the one you are desperately trying to communicate. This is Legris’s description of the birds.

In Keats ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, a similar situation is being played out, although his is a reaction stumped by bird’s song; his response to it, he knows, will be ineffectual. He pays homage to the emotion the music stirs in him, all the while knowing that he will never understand the systems at play that make the sound occurring around his ears: ‘I have ears in vain / To thy high requiem become a sod.’ Legris’s very different technique is to try to understand, via dissection and scrutiny, not only the bird’s body, but the human body hearing it, too. In this way she provides an extension of Keats’s thinking, or at least a branching from it: both poets attempt to discover the workings of a bird’s singing, and seek to understand the workings-out themselves. In the ‘Hummingbird’ poems we oscillate between the bird’s innards and outer trappings, stripping its make-up head to tail, or, at least, stripping the make-up of the bird’s song and the places out of which it emanates. These studies of the bird’s anatomy evolve into descriptions that feel intentionally close to a human physiognomy, creating a tigerish pattern of fused and spliced-together bodies. Elsewhere in the pamphlet we take ‘A trip down the slick slipping synovial slide’ (‘Where the Neck (really) ends’) – the meat of a throat bisected to reveal the intricate biological processes at play that make the noises we hear warbling from the trees. In ‘Hummingbird 1’, we encounter seven lines describing birds’ sounds and it’s all build up: a ‘stammer’, a ‘stuttering chase call’. Suspense is written through the slow bulbing motion of air coming up the throat of a bird about to sing, as though we’re watching the requisite parts of its body, the strange intricate details – flaps of flesh, movements in arteries, membrane shifts – pull together or separate in preparation for the symbiotic physical reaction that is about to take place. And all this, we’re reminded, while the bird is already making noise through another impossibly intricate bodily function, its ‘hover’. From being ‘Deep-keeled’ in the ‘bronchus’ of the bird (which is where we start), we venture through its dissected body (the wings, capillaries, the ‘lungs’ that ‘hum red’), finally finishing again inside the throat, tapping darkly on the ‘bronchiole tree’, ‘deoxygenated’, in ‘red sap’. It’s like standing next to a surgeon, vet or taxidermist, noting rapidly their needle-like slices, their precise extractions.

Her physical dissection of animal anatomies is one played out through a dissection of human language. Her exercises in synonyms go way beyond regular thesaurus usage. In an interview, she talks about her interest in the etymology of a word, ‘how it might have migrated from one area of science to another’, and in Pneumatic Antiphonal’s case in particular, ‘the correspondences between medical and ornithological terminology’. The fast turns between the words towards differing, various associations and meanings creates a deep mat of fabrics, noises, textures and references, bouncing from a nod to the limits of prosody (‘Contradiction in terms of feet. Short-syllable Apodiforme’) to a curt metaphor: ‘Humming carbuncle’. The human-made history of categorising and our urge to demarcate – via terminology and etymological play – is the focus and the poem’s event, and in this both animals and our use of them in poems is writ plainly. Their use is centred.

*

For however long we’ve written about animals we have robbed them of themselves, and we will continue to do so for as long as we write about them. They are language-less to humans, unheard beings that have nevertheless walked and swam and flown alongside us, existing as meaningful symbols in our immediate sightlines for as long as we’ve been able to mark their likeness onto a cave wall. We have seen ourselves in them and learned from them, and continue to do so. Less now, perhaps, than we did. The animal as an autonomous object, existing on its own and for itself, is something that has been marginalised, systematically and extensively. Agency is a human concept; we can’t give agency to an animal, no matter how zoo, safari or free-range egg copy would try to convince you otherwise. With animals, the biggest agency we can gift them would be to leave them to it. Too late for that. So how do we rectify the histories and marginalising factors that have led to the state of animals now?

In ‘Hummingbird’, the reference to James Audubon – ‘Song sung Audubonic’ – seems to underpin this tension, and that of the pamphlet as whole. One of the most important figures in ornithography, his Birds of America is a comprehensive and significant visual work of natural history. His aim, stated at the outset of the project (around 1820), was to paint and document every bird he encountered in North America. His paintings are obsessive in detail, gloriously coloured; moving and dynamic images of birds in their natural habitat. Except that they weren’t in their natural habitat. Every single bird he painted had been shot, stuffed and held in position by elaborate wire structures. Her testament to his work lies in both her obsessive raking over the words, so that we can try to see and respect animals again, in a new way, and in her acknowledgment of the steps we have to take to study them: stringing them up with wire, pinning their open bodies down onto a page. Such is the paradox of wanting to write about animals, or the history of animal study.

John James Audubon Letters and Drawings, 1805-1892, MS Am 21 (50), Houghton Library, Harvard University

‘Song sung Audubonic’ is a tongue-twisting three-word cosmos that holds within it human, animal and art. The slippage from ‘song’ to ‘sung’ – a familiar, yet strange decline from a noun to verb, present to past – holds within it the sadness of failing to represent, the urge to do it, and the impossibility of showing something as it is. To punctuate this whirring phrase with Audubon’s heavy, recognisable name stunts this thinking, but also works retroactively to prove the blooming effect of human language, and orality; to say it out loud and feel the strange things it does to a mouth brings my mind right back to her descriptions of biological processes of the throat, the things that work inside of us to let our voices out. She allows us to read them, hear them, and then experience them. ‘Audobonic’ is itself a very Legris-esque kind of word. It holds within it a complex pattern of syllables; with that long ‘au-’ modulating into dissonant, jarring consonants, lengthy and rushed in succession, demanding both that we halt our reading and experiment with sounding out the word. It reads almost like an anatomical or biological term, feeling close to ‘bionic’ (OED: ‘of or relating to living organisms’) or the artificial ‘biotic’. And Legris has refashioned animal sounds as though pulling them through a machine, presenting association as an inevitable urge: the workings of human interpretation are laid flat as a bird’s insides. She matches the human body to an animal’s, laying them side-by-side – we both make noises, we’re both made of meat.

This is poetry that might still say more about us than the animal, but it acknowledges this relegation. It is in her acknowledgment that the thing we’re telling will never be the thing it actually is, that the animal’s body becomes radical and altered. Keats knew it, when his painfully charged ruminations on a Nightingale’s song turned out to be ‘just a vision, or a waking dream’ – the ‘anthem’ he recounts not the bird’s at all but of his own imagining.

Hummingbird

by Sylvia Legris

Hummingbird

1

Deep-keeled. A nickel’s weight of charm and troubling. Airway territoriality. Pendulum arc bronchus flit. (Left, right, two-step flight.) Ventral symmetry.

2

Vocal fold ventriculus: hover assimilates hum. Tin ear tune an agonistic buffer.

Buzz note vocalization. Wing-box stammer. Stuttering chase call.

*

Hummingbird 2

1

Three-gram refraction. (Pulsatively breathtaking). The jewel-necked vocal nexus a complex harmonic of nectar and reflecting. Wings fan flashes of fire. Rapid

hovering exhalations.

2

Exhilaration of capillaries. Song sung Audubonic. Lyrically alveolaric.

3

Color flutters three hundred breaths a minute the lungs hum red. Glittering fragments. Vignetting gems.

*

Hummingbird 3

1

Contradiction in terms of feet. Short-syllable Apodiforme. Choriambulatory chorus. Humming carbuncle. Tongue to the trumpet blossom. Flame-licked. (Ruby-tipped stylus.)

2

Tap tap the bronchiole tree. Deoxygenated orchestral. Red sap surfs surfactant. Sip, hover, slip

through windpipe and reed. Sound peregrination.

3

Elliptically migratory. Follow the floral artery. Flight strung with Paintbrush, Blazing Star, Torch Lily. (Bloom synchronicity.) Crimson stung metabolic.

From Pneumatic Antiphonal (New Directions, 2013). Reproduced with permission of the author.