Prac Crit

Sein und Zeit

by Peter Robinson

Deep Note

by Peter Robinson

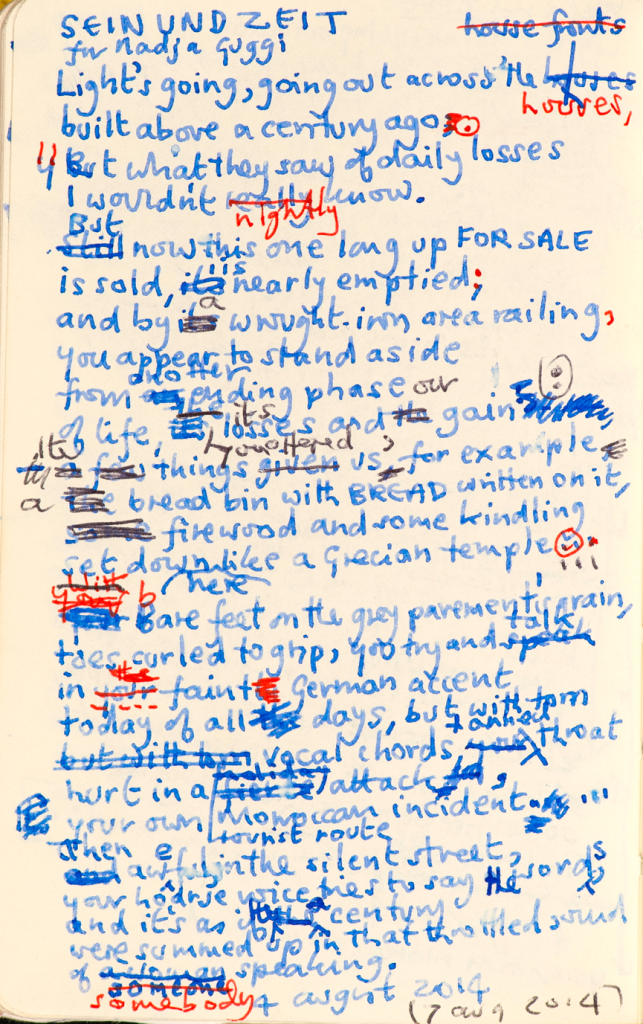

‘Sein und Zeit’ is a poem that characterizes some of the things that happen when I manage to write, and has the added benefit, for me at least, that it came fairly promptly and found a form I liked. Among my favourite poets is Umberto Saba, inventor, as far as I know, of lyrics shaped from a short opening stanza, then a longer development of the stated theme, and a concluding line, or couplet, or brief verse. I had first encountered it as borrowed by Vittorio Sereni for a number of his lyrics. Almost as soon as I’d drafted the first few lines in my notebook a day or two after 4 August 2014, it seemed the poem might evolve into such a form, though it was only during the revising that it achieved its chiastic shape, like an ABBA rhyme scheme, in which the opening quatrain and octave is then matched by a reversed octave and quatrain. As I say, it came quickly, and though I retained the date ‘4 August 2014’ at its foot as part of the poem’s meaning, there is a nearly completed draft with multiple layers of correction in different coloured pens dated Thursday 7th. The poem needed condensing by three lines; it needed to lose some overemphatic rhymes, and to have its middle eights adjusted; and it was all but done on the following day.

It is dedicated to Nadja Guggi, the typographer and designer for Two Rivers Press, with whom I have worked on a number of poetry books and anthologies. As the poem notes, she had recently been able to sell her terrace house, just around the corner from where we live, and we had been invited to go and collect some things that she was giving away – which we happened to do in the early evening on the one hundredth anniversary of Britain’s declaration of war with Germany. Nadja is a native of that country, now permanently resident in this one, and the coincidence of my wife and I visiting her on that day, of all days, had already struck me as we walked along the east-west facing street leading up towards her house. The sun was beginning to set, the roofs of the east-facing terrace casting into shadow most of the west-facing façades, façades still caught by the sun’s last rays.

‘The lamps are going out all over Europe, we shall not see them lit again in our life-time,’ Sir Edward Grey is reported to have said one hundred years before. The sunset reminded me of his remark, while, despite the WW2 song ‘When the Lights Go on Again (All Over the World)’, it’s possible to wonder whether, in the metaphorical sense that the British Foreign Secretary meant, we have seen them lit again yet. The terrace houses in the streets around where we live were built by the firm of Huntley & Palmers in the Edwardian era to house their workforce, and the nearby St Luke’s church hall has a brass plaque inside which records that it was used as a clearing station for the wounded repatriated during the 1914-18 war, doubtless because the Royal Berkshire Hospital is just a few hundred yards further on. Volunteers and recruits for the local regiments will have come from these terrace houses; but how many of them were the locations of family mourning, no, as the poem admits, I wouldn’t know.

Although I have done little more than leaf over the pages of Martin Heidegger’s Sein und Zeit (Being and Time), I happened to have recently re-read his essay entitled ‘On the Origin of the Work of Art’ for an aesthetics study group, and have a passing acquaintance with some of his more familiar concepts, such as that encapsulated in the expression ‘Dasein’, or ‘being-there’, and I’m aware too of his compromised associations with National Socialism. So I was to some extent primed, you might say, to be struck by a number of coincident things as Nadja stood on the pavement outside her house in a little black Greek-style summer tunic-dress and bare feet, with the useful objects we were taking away placed on the pavement, explaining to us why she had such a hoarse-sounding voice, and was finding it so difficult to speak.

In Heidegger’s essay there’s a homage to Greek temples and a discussion of Van Gogh’s boots, the difference between the boots and the painting of them, prompting thoughts about the being of things in themselves, their having art-significance attributed to them, and their use function, as well as the relation between the usefulness of objects and the usefulness of the words that name them, the bread and the bread-bin and the word ‘Bread’ on the bin – and of words in speech acts, such as explaining (as Nadja was), and the same words in poems, that can explain too, but also ‘condense’, which, Ezra Pound’s ABC of Reading first informed me, is the meaning of the German word ‘Dichtung’ (poetry). Hence the difference, too, between what I am doing now, and what I was doing when composing the poem. And, though I didn’t know it at the time, there is, it appears, an expression used in their classical studies: ‘griechischen Figurengedichte’ (Greek figure-poems) – of which my ‘Sein und Zeit’ might be an unconscious imitation.

It turned out, as my poem does its best to catch in a compact and evocative way, that Nadja had been on holiday to Morocco and, while camping in the desert, had awoken to find someone attempting to strangle her. Another coincidence there – I will have thought – vaguely recalling the Agadir, or Second Moroccan Crisis, of July 1911, one of the many causes of the First World War, when the German government sent their gunboat, the Panther, in response to the massing of French troops in the interior. Again, the report of that violent incident, overlaid with the temporarily averted threat of war, seemed symbolic of individual experience under the shadow of public events, and especially for women over the last century (and before), when vulnerable subjectivities have endured many forms of suppression, a suppression that can render what isn’t quite said even more expressive. And this might be an exemplary instance of when lyric poetry finds it has something to say, not least because it too occupies such a marginalized position in our commercial-technological world.

So the scene was set: a woman is standing before me, trying to speak, a victim of aggression and co-national of a country that has twice in the last century been concertedly aggressive towards my own, and, in retaliation, vice-versa. Her being and our time have been yoked by violence together. The lyrical subject, indicated as it appears only once, immediately to withdraw by means of that shrugging expression in the fourth line, has attempted to turn his poem, through its second-person address, and allow the other figure to speak in it; but she can’t (it’s a lyric poem, and she’s half-strangled), so he has to write in such a way as to try and evoke her vocalization – in which endeavour he is, strictly speaking, bound to fail. Then he has to show the poem to its dedicatee and hope that she isn’t offended by its obliquely epideictic presumption. And the fact that you have read it here means, I’m relieved and grateful to report, that she wasn’t.

Sein und Zeit

by Peter Robinson

for Nadja Guggi

Light’s going, going out over the houses,

built above a century ago;

yet what they saw of attrition’s losses,

no, I wouldn’t know.

But now this one long up for sale

is sold, is nearly emptied;

and by a wrought-iron area railing,

you appear to stand aside

from the few things offered us:

a bread bin with BREAD printed on it,

firewood and some kindling

set down like a Grecian temple…

Bare feet on the grey pavement’s grain,

toes curled to grip, you try and talk

with your faint German accent

today of all days, to explain

the choked tone’s from torn vocal chords,

then rub a suntanned throat

hurt in that tourist route attack –

your own Moroccan incident…

You try to say the words,

and it’s as if a hundred years

were summed up in the half-throttled sounds

of a woman speaking.

4 August 2014

First Published by Prac Crit.