Prac Crit

The Silver Birch

by Liz Berry

Essay

by Edward Doegar

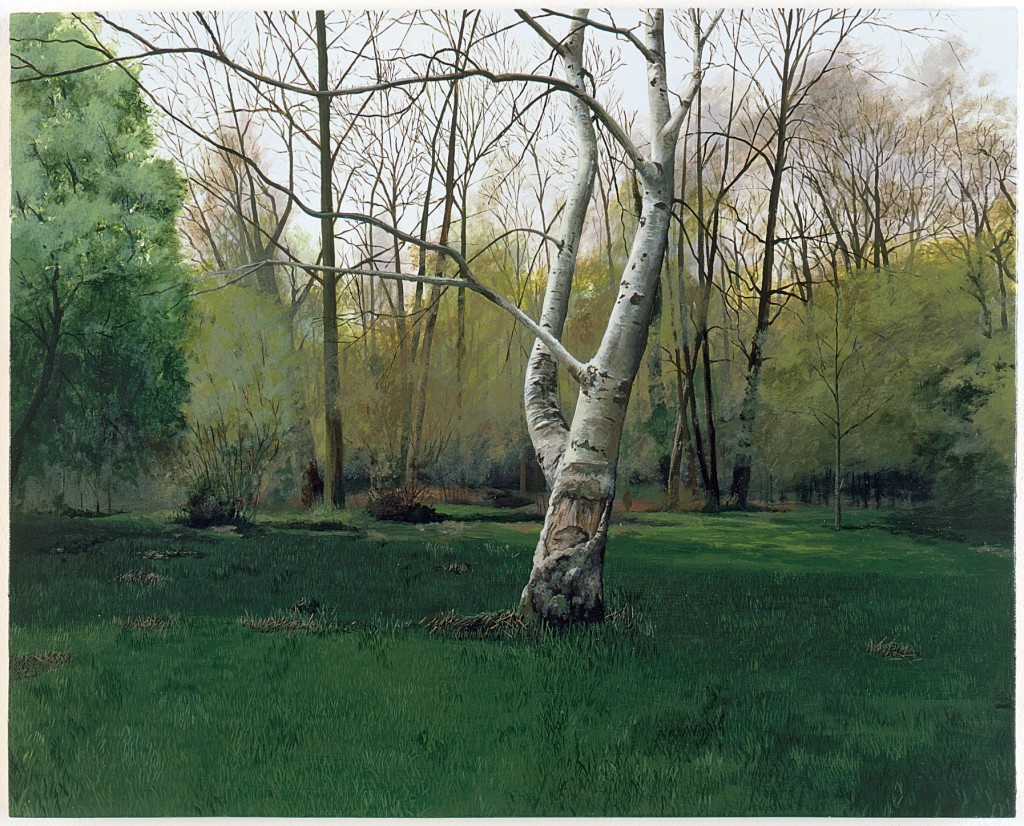

George Shaw, ‘The Silver Birch.’ © The Artist. Courtesy Wilkinson Gallery, London.

Beginnings matter. Liz Berry opens ‘The Silver Birch’ with the strange self-defeating logic of paradox: ‘Let me tell you about the sex I knew / before sex’. It’s a tease worthy of John Donne: a perfectly understandable contradiction, which both frames and veils the rest of the poem. Yet despite starting out in this mode, Berry eschews the neat and witty resolutions of the metaphysical school; instead, as the poem unfolds to elucidate those lines, each clarifying metaphor only adds to the confusion, and the narrative spirals away into a reverie of remembrance and ecstatic expansion.

In the very next line, Berry is beginning again, a gesture all the more emphatic because of its heavy Biblical precedent (‘in the beginning’). And so, gradually, the poem becomes a series of beginnings that are all disconcertingly un-sustained. The next phrase introduces a conceit (‘when I was a creature’) brought thrillingly alive as the speaker describes taking ‘the bit of your hair / between my teeth’ only for this horse-self to transform into a furred animal (a fox?) in the ‘dens and copses’ and then be dropped altogether as the speaker becomes ‘unwritten upon paper’, ‘a pond’. And just as Berry changes her metaphorical transport, so the speaker’s agency flits from commandingly violent possession (‘I took the bit of your hair / between my teeth… while you whimpered’, ‘I held your fingers in my mouth’) to being the object of possession (‘sex was a pebble thrown / into the pond of me’, ‘my body was a meadow then / and you could lie in me forever’).

The crisp opening paradox has been reworked into a messy profusion of adolescent experience, but it is confusion by design. After all, what could be truer to adolescence than this restless over-identification of the self? The deliberately curtailed extended metaphor is just one more technique. Berry is impressively promiscuous in her poetic borrowings; she moves freely between paradigms of sense, from the baton passing of association to the nested dolls of parable, enjoying the game and ignoring the rules. The poem, though loudly lyrical, also offers a quiet gathering of allusion and technique which underwrites its cumulative power. Many of the references, if not hidden, are hardly foregrounded. This confidence in her own re-imagining is something Berry shares with George Shaw, whose painting inspired the poem. The painting, also titled ‘The Silver Birch’, is one of a series of obliquely religious paintings called ‘Scenes from the Passion’. 1 Shaw’s paintings from this series are imbued with the atmosphere of their title; while the paintings are set in the liminal spaces of the painter’s youth in Coventry and share little obvious iconography with traditional representations of the Passion, they achieve a Baroque profundity of attention that recalls the sacred. In a similar way, Berry’s language navigates the deep resonance of religious emblems without them ever quite becoming fixed points.

The juvenile pastoral becomes an Eden-esque setting: what was established in the foundational echo of Genesis tolls again in the lines ‘everything was sex then / although I could not name it’. The couplet is an interesting inversion of the Garden of Eden, where Adam named the elements but had yet to experience knowledge. The poem is a prelapsarian rhapsody and in this context the climax of innocence is its loss. The backwards look of the opening lines and the repeated emphasis of the past tense (‘those days’, ‘everything was sex then’, ‘my body was a meadow then’) ensure the poem throbs with loss. The memory of erotic awakening transforms the place of its happening – hence Berry’s use of the pathetic fallacy: ‘the woods hummed electric with sensation’. But Berry takes this one step further, letting the speaker actually become the environment. The poem is a sort of M.C. Escher illusion, a figure in a landscape in which desire keeps alternating the perspective.

Read from a New Testament point of view, 2 the landscape of innocence and the transcendence of sex are suffused with suffering and the oblivion of death. There are gentle hints towards the agonies of the Passion: the title ‘birch’ suggests flagellation and this, presumably, leaves its mark in the ‘scar upon your shoulder’. From these gestures of suffering we move onto pagan visions of Elysium’s everlasting fields (‘lie in me forever / and still not be done’). The poem’s ending is an unending climax, a suspended Fall achieved through echoes of the Ascension. Seen in these terms the stakes of this (pre-)erotic epiphany are absurdly high and yet what makes it so compelling is the lightness with which it’s achieved. The poem is religiously emboldened without being theologically bound.

In part this is because Berry draws on the tone and textures of the English lyric tradition as a tempering influence, to offer an alternative mode of transcendence. That lone adolescent figure in the landscape 3 seems to follow Wordsworth’s Intimations of Immortality, in which he rails forth with youthful solipsism to sing lines of fevered lyricism (‘To me alone there came a thought of grief’), over-identifying with his surroundings (‘The fulness of your bliss, I feel – I feel it all’). Berry’s own breathless Romantic urgency makes each line reach for an ever higher note: ‘sex was a pebble thrown / into the pond of me / rippling out’. But it is perhaps the poets of the First World War whose influence guides the phrasing and tone of her poem most keenly. The ‘dens and copses’, ‘cuckoo spit’ and ‘jack-in-the-hedge’ seem reminiscent of Edward Thomas’s meticulous notation, and Berry’s melody of nostalgia laments a lost England, almost as much as a lost Eden. Berry borrows the emotional resonance of that national loss (‘Never such innocence again,’ Larkin said in ‘MCMXIV’) and the redemptive transformation of the sublime as she recalls the phrasing of Siegfried Sassoon’s masterpiece ‘Everyone Sang’. She prepares us for it in ‘now they sang now’ and ‘every bowing poppy’ so that we hear Sassoon’s ending (‘O, but Everyone / Was a bird; and the song was wordless; the singing will never be done’) in her own:

oh my body was a meadow then

and you could lie in me forever

and still not be done

It’s an ending that lasts and lasts. It’s so convincing, happening so vividly, so ecstatically, that the melancholy untruth of it takes a moment to sink in. The heavy then-ness of the experience undoes the eternity of the feeling. So we end, as we began, in a paradox – and one which illuminates the terrible and banal poignancy of memory: that what lasts has already been lost.

Notes:

- Berry has written several poems in response to Shaw’s ‘Scenes from the Passion’ series. In her debut collection, Black Country, the following poems were all inspired by Shaw’s paintings of the same title: ‘The Assumption’, ‘The Way Home’, ‘The First Path’, and ‘Christmas Eve’. Berry has written about the process here. ↩

- Of course ‘in the beginning’ not only echoes Genesis but John’s Gospel too. ↩

- Whilst there are clearly two people in Berry’s poem, the speaker and addressee, the majority of the poem dramatizes a singular figure in the landscape, so much so that the speaker identifies herself as the landscape to accommodate the addressee. ↩

The Silver Birch

by Liz Berry

Let me tell you about the sex I knew

before sex

in the beginning when I was a creature

when I took the bit of your hair

between my teeth

and pushed your face to the silver birch

while you whimpered

at the fur of me

how I came alive in dens and copses

in the tall grass

where the sky lurched violet

yes those days

when I was neither girl or boy

but my body was a sheaf

of unwritten-upon paper

now folding unfolding

origaming new

days pale as the silver birch

when sex was a pebble thrown

into the pond of me

rippling out

when I held your fingers in my mouth

as the woods hummed electric with sensation

now they sang now

and everything was sex then

although I could not name it

it was the scar upon your shoulder

an arrow of light through the beeches

days days wet as cuckoo spit

when I lay skin-bare in the field

each insect jack-in-the-hedge

every bowing poppy touching me

oh my body was a meadow then

and you could lie in me forever

and still not be done

From Black Country (Chatto & Windus, 2014). Reproduced with permission of the author.